Voluntary Severance: a very quick data blog

Lots of Universities are not shutting Departments, but instead offering voluntary severance to the whole academic staff body. I’ve been considering whether there is a way to work out how Chemistry might be affected by this approach. It’s less headline-grabbing than shutting a Department, but it may be that Chemistry Departments are salami-sliced in ways which damage staff effectiveness in doing the demanding work of teaching and researching Chemistry.

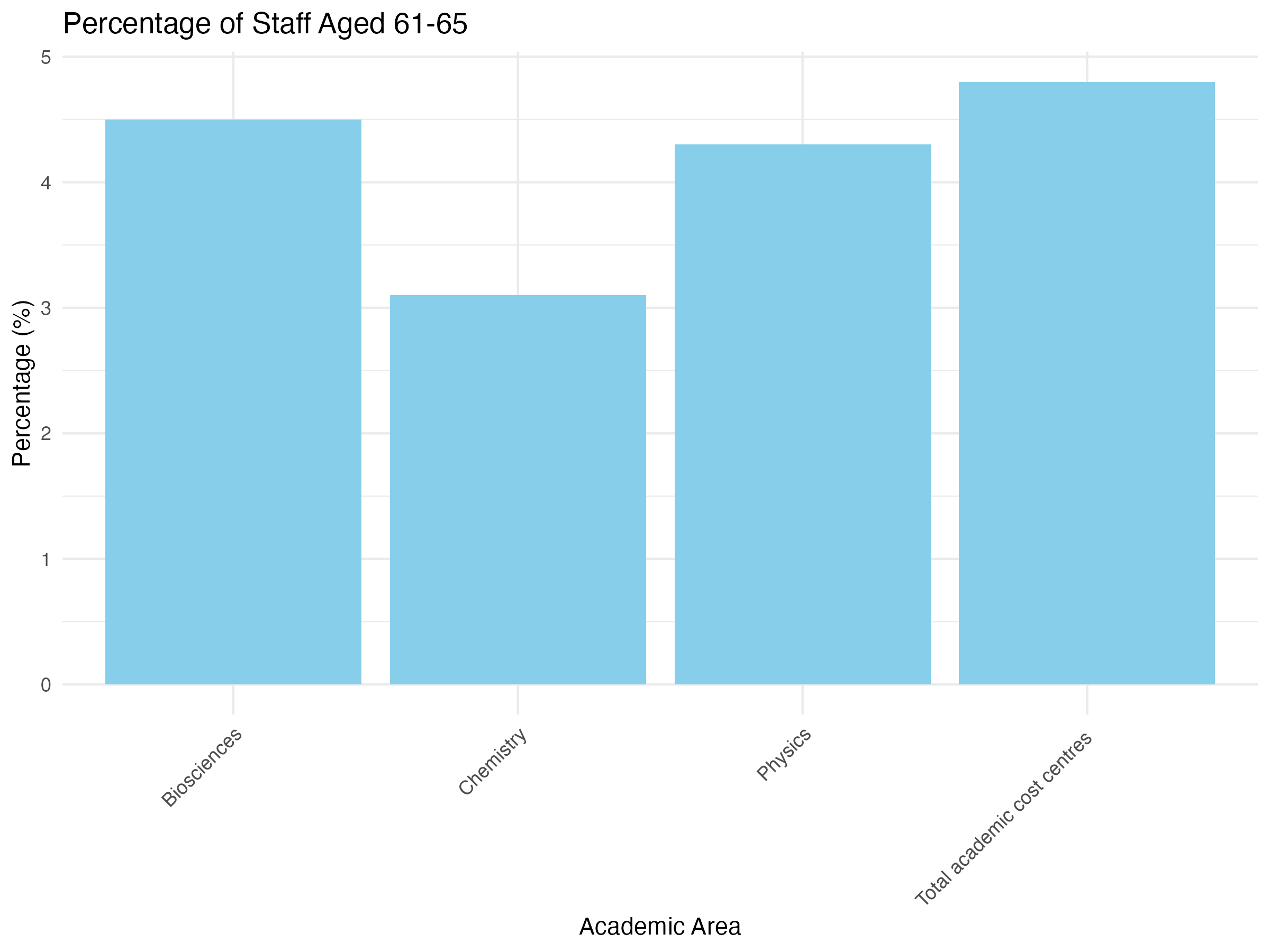

First I thought I’d see whether near-retirement age groups were over-represented in Chemistry. Using the 22-23 HESA data, I gathered the Biosciences and Physics data for comparison as well as the total academic populations. My reasoning was that staff near retirement age might be more attracted by the lump sum of a severance payout. Note that the current statutory retirement age in the UK is 66. (EDIT 18Dec24: there is no statutory retirement age in the UK, but the current age at which people can access the state pension is 66.)

The % of academic staff in Biosciences, Chemistry, and Physics who are in the 61-65 age bracket in the 22-23 HESA data. Also included is the % of all UK Academic staff in this category. Statutory retirement in the UK is at age 66.

Chemistry apparently has fewer staff in the 61-65 age bracket than other subjects. It may be that this serves the subject well in an era of voluntary severance.

Next I plotted the % populations of staff in part-time roles. My reasoning was that the income lost from severance might be numerically smaller than on a full-time contract. To be very clear: I am not suggesting that part-time staff are less dedicated to their work; it is well-established that over-work is a much more significant feature of part-time academic contracts than it is of full-time contracts.

The % of academic staff in Biosciences, Chemistry, and Physics who are on part-time contracts in the 22-23 HESA data. Also included is the % of all UK Academic staff in this category.

Chemistry has a (much) smaller proportion of part-time staff than other subjects, even in the sciences. This seems bad to me from an equity perspective, but for the narrow analysis of voluntary severance schemes it may be that this serves the subject well.

The last demographic group I plotted was the % of disabled staff. My reasoning here was that marginalised staff may be more inclined to leave than included staff. Again, I am not suggesting that disabled colleagues are less dedicated to their work. I am only suggesting that sometimes workplaces do not live up to the inclusive hopes we have for them, despite legal provisions like the Equality Act.

The % of academic staff in Biosciences, Chemistry, and Physics with a declared disability in the 22-23 HESA data. Also included is the % of all UK Academic staff in this category.

The % of disabled academic staff in Chemistry is similar to the other sciences, but lower than the total academic staff body. Again, I think this should be described as a failure in these Sciences. If voluntary severance encourages disabled staff to leave, perhaps Chemistry is protected from the current stormcloud. At the same time, this data suggests that disabled staff either didn’t join these Sciences or didn’t stay; we should be worried about this as a community.

My last analysis was to work out what % of a University’s staff were associated with the Chemistry cost centre (113). My reasoning where was that a University looking to shed a certain number of staff will likely shed more people from their bigger Departments.

The % of staff within each University associated with the Chemistry (113) cost code in the 22-23 HESA data.

There is a wide range here, but it is striking to see that some of the Universities currently offering voluntary severance have a high % of their academic staff in Chemistry. It may also be that details of accounting are important here. If a University hired academics through a contracting agency to deny them equitable working conditions, for example, these staff would not be considered as being employed by that University.

I’m not sure this is tremendously meaningful, but if you add all the % values together you get about 160%. It is interesting to consider whether it’s useful to describe the UK having about one-and-a-half Universities of Chemistry. But it is urgent to consider how the shrinking of the UK’s University sector is going to play out for a subject which largely failed to grow during the last ten years.