On Lecture Recordings

I’m applying for jobs at the moment, and am experiencing the distinctive agony of reflecting on how I might have answered interview questions better.

A recent question I had was on lecture capture, specifically my view of it in a Chemistry department. I can’t go back in time and change what I said. But it’s an interesting question and I can write a therapeutic blog post about it.

Historical and Policy Framing

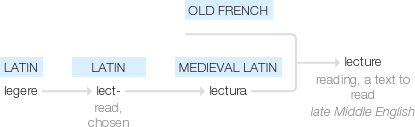

The traditional lecture was designed to disseminate hard-to-access material at scale. The original lectures were recitations of books so students could make their own copies; the etymology of ‘lecture’ derives from the latin verb ‘to read’. Lectures’ position in educational contexts after Gutenberg was cemented by the way that the format could exploit the expertise of staff to deliver a time-efficient piece of content-rich teaching to students.

An etymology of ‘lecture’, drawing on the medieval latin verb ‘lectura’: to read.

In modern massified Higher Education this scalability remains its central merit - you can lecture to twenty students as easily as a hundred. This is not true of most pedagogies (good luck doing a hundred-person workshop), but scalability relates very closely to how didactic the pedagogy is: lectures embody a way of teaching where one academic says things and (any number of) students hear things. This can be a transformative experience - most of us have sat in an inspirational didactic lecture at some stage - but normally it is not.

Practicalities and Analysis

Of course there are inventive ways of disrupting the lecture. Incorporating worked problems into lectures is a common way of trying to adapt lectures to Problem Solving outcomes within the conventions of traditional timetabling. ‘Flipped’ lectures are a more aggressive response to the same challenge. Some of the decolonisation strategies such as representing diverse thinkers in lectures don’t challenge the didacticism of the traditional lecture format, but arguably honour the thematic ambition of active learning by centring the lecturer less.

Conceptually, lecture capture locks you into the didacticism of the traditional lecture. As a policy ambition it isn’t clear to me that online teaching is best done by ‘capturing’ what we do in person - the affordances of online learning are vast. A recorded lecture could be substantially improved through modest changes such as making several short videos with high-quality audio and professional subtitling instead of one hour-long lecture in a ‘boomy’ theatre with auto-transcription incapable of representing sophisticated chemical nomenclature. If we were going to do online teaching really well, what choices would we make about how to deliver the material currently taught through lectures? “Lectures but recorded” might be a weak answer to this question.

Even so, lecture capture is much more inclusive for students who can’t make it to lectures, which is an unalloyed good. At the same time, it is not always done well; my students tell me that sometimes a captured lecture has no (or poor) audio. Is it inclusive if it’s done badly? What training is (still) needed to make lecture capture deliver the inclusive teaching we had hoped it would? Doing online learning well takes time and doing it from scratch requires a community tuned into the peculiar subtleties of online education; a big attraction of lecture recording is that it is not much extra effort when you’re lecturing anyway. In a curriculum built around the rapid dissemination of knowledge being assimilated by students, it might be that the management of staff time is calibrated around the efficiency of one-and-done lecture delivery.

Student Behaviours and Educational Intention

The biggest worry for me is that if asynchronous engagement is systematically introduced to a synchronous curriculum, the new incentives and patterns of student behaviours need serious thought. Are you examining the content of lectures or the content of the syllabus? This question becomes incredibly important if students can re-watch lectures. How many hours a week should students be working? Do you allow them new workload time to re-watch lectures when you estimate their workload? (Will students watch lectures again rather than reading a book?) Or do you recognise the opportunity to listen to lectures at 1.25x speed and allow less workload time to engage with lectures? Is it the same thing to watch a lecture a week per topic as it is to binge-watch a whole lecture course in one sitting? In a discipline with 10h of lectures on a quiet week, the answers to these questions are really important.

Some of the student behaviours in the first lectures still seem enjoyably recognisable today: studious listeners sit beside people chatting, sleeping, staring into space.

Which perhaps brings me to the answer I gave in my interview. I am fairly ambivalent about the question of lecture capture (with the exception of its use to include students unable to attend or hear lectures, which I endorse without much reservation so long as staff are adequately trained). The reason I am ambivalent about it is because it’s the kind of question which often distracts us from more strategic educational principles. The pedagogy should be the last piece of the puzzle, after intention and assessment: lecture capture is an interesting cart, but we really need to talk about the horse.

So if a Chemistry degree wanted to teach scientific problem solving and assessed this through timed exams, it might abandon lectures (or record high-quality materials to replace them) to free up staff time for workshops. If a degree wanted to emphasise factual recall as judged by three hour papers on broad topics like the periodic table it might see traditional lectures as a good tool (and recorded lectures a good accommodation). If a course wanted to address poor mental health in first years, it might make every effort to encourage the daily routine established by 9am lectures (and perhaps only provide lecture recordings to those who asked for them). If a course wanted to centre out-of-sequence tutorial teaching, it might provide last year’s recordings to students who have their tutorials scheduled before the lecture course in that topic.

You may disagree with some of these examples, but my central point is that it’s useful to describe lecture capture as a tool: judging its value can only be done in the context of a course’s intention and assessment. What does a chef think of a potato peeler? Are potato peelers good? Yes, if you are peeling potatoes. No, if you are ladling soup.

Conclusion: a Chance to Listen not to Lecture

Discussing the specific issue of lecture capture often allows us to hear - implicitly - what someone thinks education is about more generally. This chance to listen to each other is the exciting bit about any pedagogical innovation for me: we are given a chance to express what we think is valuable about both what we’re currently doing and also what we might do. Perhaps the balance of opinion sits in favour of lecture capture, perhaps it doesn’t. But talking about it helps us build a sense of what we hope to accomplish as individuals, and the messy act of compromise helps us build community (if we compromise graciously).

Ironically, imposing lecture capture as a central top-down policy shuts down a lot of the valuable conversation in much the same way that a didactic lecture shuts down a lot of the scope for active learning. Reasonable people will be able to find some resolution to a proposal like lecture capture, and any good teaching community will be able to make the case for inclusion in ways which honour both the needs of students and the reflective perspectives of colleagues.

I personally think the merits of lecture capture are good enough that Chemistry Departments should generally do it. It’s a low-disruption way of enhancing inclusivity at scale, and helps Universities to satisfy the demands of the 2010 Equality Act. There are certainly other ways of accomplishing these goals, though, and I’d be open to exploring them with colleagues so long as disabled students weren’t excluded by the delay.

What this answer reveals about me, I think, is that I see equity as a central part of high-quality education and pragmatism as a central principle of educational decision-making. I’d always be keen to see what other answers revealed about other people.