Ten years of £9k fees: How has Chemistry fared?

Policy Context

In 2012, the Conservative Universities Minister in the coalition government successfully raised tuition fees from about £3000/year to £9000/year. £9k fees would only be permitted if Universities widened access to HE, welcoming students from backgrounds they had traditionally served poorly. Without advancing the access agenda, Universities were restricted to £6k fees, a theoretical possibility which was not taken up by many institutions.

Even more importantly, the new fees were coupled with a lifting of the numbers cap in Universities. The hope was that the market could sustain Higher Education when a cash-strapped government couldn’t. The £9k wasn’t new money, it just shifted the cost of HE from the state to the student.

It is striking to read contemporary accounts of this change: the eye-watering student burden mostly saved universities from the most desperate effects of Austerity policies advanced after the 2008 financial crisis, but also accelerated a swing towards framing education as a consumer product. It probably also remains the stand-out event in the collapse of the Liberal Democrat Party’s electoral success, as they had promised before the election to vote against tuition fee increases.

This blog explores the UCAS data for applications and accepted offers since 2012. Has Chemistry exploited the rise in student numbers in the good times? As we stare at the looming cost-of-living crisis (with the value of tuition fees likely to be eroded by inflation rates soaring over 7%) does Chemistry enter a time of constrained resources from a position of strength?

Data and Devolution

I have used the UCAS data here, which includes Universities in all four nations of the UK. While Education is a devolved matter, UCAS is not a devolved institution (Universities in all four nations of the UK are in here, despite tuition fees not being at the £9k level for all students). The language in this blog includes Scotland, for example, which charges £9k to students from England despite not being directly bound by English HE policy.

Application Numbers

Total UCAS application numbers have risen since 2012, with the year-on-year bumps settling around the 3 million mark. Applications within the Physical Sciences grouping of subjects have been steady at about 100,000. This more-or less matches the Medicine and Dentistry application numbers, but falls significantly short of the Biological Sciences grouping. Biological Sciences subjects have experienced a substantial increase in applications since tuition fees rose.

Applications by subject (at the JACS3 level) are interesting. Chemistry application numbers swelled immediately after 2012, but have declined since. In contrast, application numbers for Biology, Physics, and the JACS3 code including Biochemistry have risen steadily over the whole ten years.

Accepted offers

The same patterns play out in the number of accepted offers in the UCAS data. While there were more accepted offers over the last ten years, this has not been true for Physical Sciences. Chemistry acceptances buoyed after 2012 and then declined, in contrast to Physics (which grew modestly) and biological subjects (which grew immodestly).

These numbers are very disappointing: at a time of historic growth for HE, Chemistry has stagnated.

Competitiveness and Market Share

Plotting the number of applications per accepted offer gives some sense of the competition for places. Each applicant can make applications to several (currently 5) courses, and most subjects (including Chemistry) have Application:offer ratios which reflect this. Medicine is an exception, being roughly twice as competitive to enter.

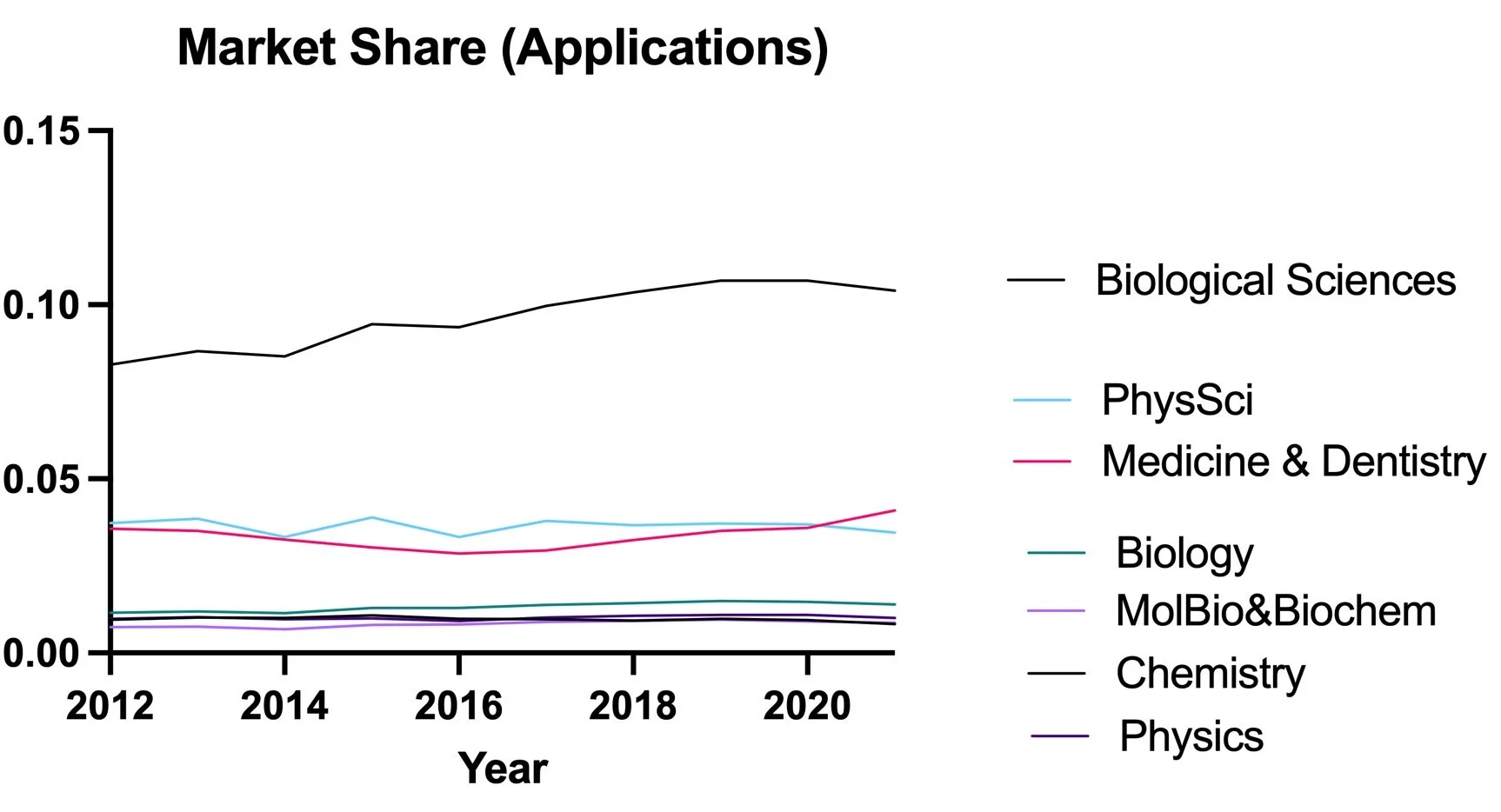

The proportion of all applications due to each subject and grouping can describe the winners and losers from HE expansion. In broad terms, Biological Sciences are winners - cruising over 10% of all applications - and Physical Sciences are losers. Increasingly, science students are Biology students.

Rates of Growth

This idea of winners and losers can be presented more clearly by plotting out the rates of growth from the 2012 numbers. Over the last 10 years - a period of massive expansion in Higher Education - Chemistry has shrunk to 98% of its 2012 applications and accepted offers. This stands in stark contrast to the growth of Biology, which has grown more than 30%. Even Physics has grown, though by a more modest margin.

Analysis

The move to a £9k tuition fee level in 2012 allowed Universities to educate more people because the numbers caps were lifted. Despite early increases in applications and offers, Chemistry has failed to grow over this decade. This stands in contrast to not only the other core sciences but also to the numbers-capped medicine. To see a shrinkage in Chemistry numbers during a period of market liberalisation is a missed opportunity to share the subject with more people; I see this as a sad thing.

Why has this happened? It seems likely that the hard constraints on specific resources have restricted student numbers: you can’t safely double the number of students in the first year labs without more lab space. Within the inflexible context of the RSC accreditation criteria, this has held back the growth of the subject; perhaps a relaxation of lab hour requirements might have allowed more people to learn Chemistry.

It is interesting to see that restricting space on Chemistry degrees has not led to an increase in competition for those spaces. Some might point to this and suggest that restricting spaces has not held back recruitment; my view is that the promotion of courses in marketised HE responds to the number of places available. We’d have more chemists if we’d had more spaces.

Chemistry should therefore think really carefully about Biology. It is right to ask whether the Chemistry curriculum is exciting enough when contrasted with Biology, but it is also important to recognise the logistical features of Biology which have allowed it to expand in the uncapped market. Biology’s lab requirements are much more flexible, the extent of PSRB standardisation is much lower, and together these features have permitted a richer offer of degree programmes to applicants.

What next?

Chemistry has missed the boat. There was a moment where imaginative action might have let us share the subject with more students every year, and that moment has probably ended. The 2012 political innovations of £9k fees and removing student number caps have shifted to a 2021 government agenda which is increasingly hostile to HE; we now have a de facto policy of squeezing funding through inflationary pressure on the fixed fee.

The boom-time growth of subjects like Biology, Molecular Biology, and Biochemistry therefore seems likely to threaten the institution-level viability of the RSC-accredited Chemistry degree. In the logic of the market, these are near-substitute subjects which are cheaper to deliver. The options for Chemistry departments in this context are all bad.

We could teach more cost-efficiently, but this seems difficult when we already rely so heavily on lectures and when labs are so totemic for the RSC. We could close Chemistry departments and perhaps support biology-aligned teaching of chemistry topics, or a pooling of resources into degrees like Natural Sciences. We could lobby for more government funding, but this seems unrealistic in the current finances of the country despite the chemical basis of many of the pandemic’s central technologies.

Perhaps there is a chance to review how Chemistry degrees are (and should) relate to the marketised model of HE. We have been outplayed by Biology, and we might learn something by thinking rigorously and radically about how they have outmanoeuvred us.